When you switch to a generic drug, you expect the same results as the brand-name version. But what if your body doesn’t respond the same way-even though the chemical is identical? For many people, the difference isn’t in the pill. It’s in their genes.

Why Your Genes Matter More Than You Think

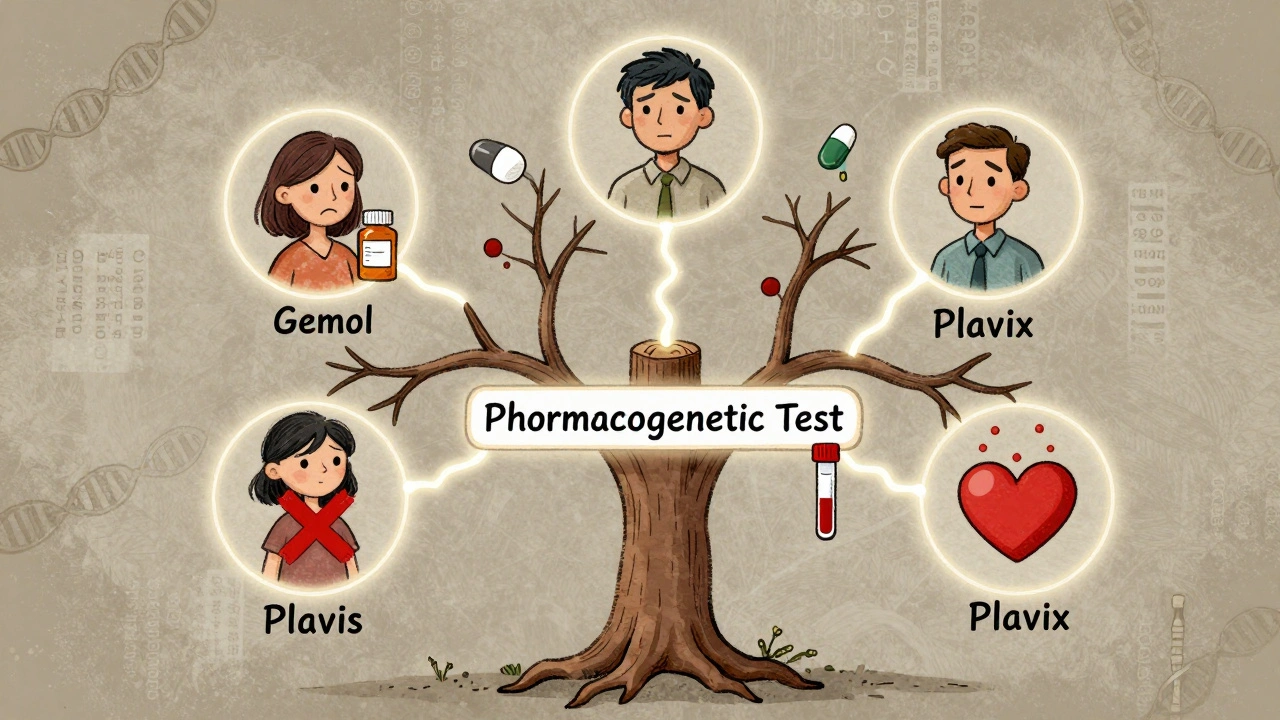

Generic drugs are required by law to have the same active ingredient as their brand-name counterparts. So why do some people feel like generics don’t work as well? Or worse, why do they get sick from them? The answer lies in pharmacogenetics-the study of how your genes affect how your body processes medicine. Your genes control the enzymes that break down drugs in your liver. One of the most important enzyme families is the cytochrome P450 system, especially the CYP2D6 gene. About 25% of all prescription drugs, including common antidepressants like sertraline and painkillers like codeine, are processed by this enzyme. But CYP2D6 isn’t the same for everyone. Over 80 different versions of this gene exist worldwide. Some people have versions that break down drugs too fast. Others have versions that barely work at all. If you’re a slow metabolizer and take a standard dose of a drug processed by CYP2D6, the medication builds up in your system. That can lead to side effects like dizziness, nausea, or even serotonin syndrome. On the flip side, if you’re a fast metabolizer, the drug gets cleared before it can do its job. You might think it’s not working, but your body is just removing it too quickly.Family History Is a Clue-Not a Guarantee

Your family’s medical history can give you a hint about how you might react to certain drugs. If your mother had severe side effects from a common antidepressant, or your father needed a much lower dose of blood thinner, that’s not just coincidence. It’s likely genetic. Take warfarin, a blood thinner often prescribed after a stroke or heart surgery. Two genes-CYP2C9 and VKORC1-control how your body handles it. People with certain variants in these genes need much smaller doses. If your parent had a dangerous bleed on warfarin, you might carry the same genetic risk. That’s why doctors now recommend genetic testing before starting warfarin, especially if there’s a family history of bleeding problems. The same goes for drugs like clopidogrel (Plavix), used to prevent heart attacks. About 30% of people have a genetic variant that makes this drug ineffective. If your sibling had a second heart attack while on Plavix, it could be because their body couldn’t activate the drug. This isn’t about the generic version being inferior-it’s about your biology.Population Differences Can Change Everything

Genetic variations aren’t evenly spread across populations. For example, about 15-20% of people of Asian descent are poor metabolizers of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole. That means they need lower doses to avoid side effects like bone loss or nutrient deficiencies. Meanwhile, African Americans often need higher doses of warfarin than white patients-not because of weight or diet, but because of genetic differences in CYP2C9 and VKORC1. This matters when switching to generics. If you’re a patient of African descent and your doctor prescribes a generic warfarin based on standard dosing guidelines, you might be underdosed. That increases your risk of clots. Conversely, if you’re of East Asian descent and take a standard dose of a generic PPI, you might end up with long-term complications. The FDA now lists over 300 drugs with pharmacogenetic information on their labels. That includes common generics like simvastatin (for cholesterol), amitriptyline (for depression), and 5-fluorouracil (for cancer). But most doctors still don’t check your genes before prescribing.

Real Stories: When Genetics Saved Lives

One patient in Leeds, after switching to a generic version of 5-fluorouracil for colon cancer, started vomiting violently and couldn’t keep food down. Her oncologist had no idea why-until she mentioned her uncle had died from the same drug. Genetic testing revealed she had a rare DPYD gene variant that made her body unable to break down the drug. Her dose was cut by one-third, and she finished treatment without severe side effects. Another case involved a man on sertraline for depression. He switched to the generic version and developed confusion, rapid heartbeat, and shaking. His pharmacist flagged it as possible serotonin syndrome. He’d never been tested, but his family history showed his sister had a bad reaction to the same drug. Testing confirmed he was a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. His dose was lowered, and his symptoms vanished. These aren’t rare cases. A 2023 Mayo Clinic study tracked 10,000 patients who got preemptive genetic testing. Over 40% had at least one high-risk gene-drug interaction. Two-thirds of those cases led to medication changes-and adverse events dropped by 34%.Why Doctors Still Ignore Genetics

Despite all the evidence, most doctors don’t test for pharmacogenetics. Why? Time. Training. Cost. A 2022 survey of over 1,200 clinicians found that 79% said they didn’t have enough time to interpret genetic results. Only 32% felt confident using HLA-B*15:02 testing to avoid dangerous skin reactions from carbamazepine. Even when results are available, many EHR systems don’t alert doctors automatically. Some tests cost $250-$500, and insurance doesn’t always cover them. But consider this: a single hospitalization for a drug reaction can cost over $15,000. Preventing one reaction pays for the test many times over. The good news? Major hospitals like Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt have been running preemptive testing programs for years. They test patients once for dozens of genes, then store the results in their medical records. Every time a new drug is prescribed, the system checks for conflicts.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for your doctor to suggest genetic testing. Here’s what you can do:- Know your family’s drug history. Ask relatives: Did anyone have bad reactions to antidepressants, blood thinners, or painkillers? Did anyone need unusually high or low doses?

- Ask your pharmacist. Pharmacists are trained in drug metabolism. Bring up your family history and ask if your meds could be affected by genetics.

- Request a pharmacogenetic test. Tests like Color Genomics or OneOme screen for 10-20 key genes and cost under $300. Many insurance plans cover them if you’re on high-risk drugs like warfarin or chemotherapy.

- Ask for your results. If you’re tested, get a copy of your report. Keep it with your medical records. Bring it to every new doctor.

The Future Is Personalized

The FDA approved the first pharmacogenomic-guided antidepressant tool in 2023. The NIH is funding $127 million in research to better understand genetic differences in underrepresented groups. By 2025, 92% of academic hospitals plan to expand genetic testing programs. The goal isn’t to avoid generics. It’s to make sure the right generic is given to the right person at the right dose. A generic drug isn’t just a cheaper version of a brand name. It’s a tool-and like any tool, it works best when it’s matched to the user. Genetics isn’t magic. It’s science. And it’s the key to making sure your medication actually works-no matter what label is on the bottle.Can my family history tell me if I’ll react badly to generic drugs?

Yes, in many cases. If close relatives had serious side effects, required unusually high or low doses, or had unexpected treatment failures with certain medications, you may carry the same genetic variants. This is especially true for antidepressants, blood thinners, and chemotherapy drugs. Family history is a strong red flag that warrants genetic testing.

Are generic drugs less effective because of genetics?

No. Generic drugs contain the same active ingredient as brand-name versions. The issue isn’t the drug-it’s your body’s ability to process it. Genetics determine whether you metabolize the drug too fast, too slow, or not at all. That’s why two people taking the same generic pill can have completely different outcomes.

Which genes affect drug response the most?

The most important genes are CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, TPMT, and DPYD. CYP2D6 affects about 25% of all drugs, including antidepressants and painkillers. CYP2C9 and VKORC1 control warfarin dosing. TPMT affects chemotherapy drugs like azathioprine. DPYD impacts 5-fluorouracil, used in cancer treatment. Testing for these can prevent serious side effects.

Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by insurance?

It depends. Medicare and some private insurers cover testing for high-risk drugs like warfarin, clopidogrel, and certain chemotherapies. For broader panels, coverage varies. Many tests cost $250-$499, and some labs offer payment plans. Even if not covered, the cost is often lower than a single hospital visit due to a bad reaction.

Should I get tested before switching to a generic drug?

If you’ve had unexplained side effects or poor results with medications in the past, or if your family has a history of bad reactions, yes. Testing before switching can prevent dangerous outcomes. Even if you’ve never had a problem, if you’re starting a high-risk drug like warfarin, clopidogrel, or chemotherapy, genetic testing is strongly recommended by clinical guidelines.

Do I need to get tested more than once?

No. Your genes don’t change. A single test gives you lifelong information. Once you know your results, you can share them with every doctor you see. Many hospitals now store genetic data in electronic records so future prescriptions are automatically checked for risks.

Can I ask my doctor to test me for pharmacogenetics?

Absolutely. You have the right to ask for any test that could improve your care. Bring up your family history, mention that the FDA recommends genetic testing for over 300 drugs, and ask if pharmacogenetic testing is appropriate for your current or planned medications. Many doctors are open to it-especially if you’re on multiple drugs or have had side effects before.

Next steps: If you’re on a long-term medication, especially for depression, heart disease, or cancer, talk to your pharmacist or doctor about genetic testing. Keep a record of your family’s drug reactions. And don’t assume a generic is always safe-your genes might have a different opinion.

Taylor Dressler

10 Dec 2025 at 14:57Just had my CYP2D6 test done last month after my SSRIs stopped working. Turns out I'm a poor metabolizer. Switched from generic sertraline back to brand - same active ingredient, but my body finally stopped feeling like a zombie. This isn't placebo. It's biochemistry. If you've ever thought generics 'didn't work' - maybe your genes were screaming at you.

Pro tip: Ask your pharmacist for the pharmacogenomic report before refilling. They're trained to catch this stuff.