When a pregnant person takes a medication, it doesn’t just stay in their body. It travels through the bloodstream, reaches the placenta, and can cross over to the developing baby. This isn’t science fiction-it’s everyday biology. And it’s why so many doctors hesitate before prescribing even common drugs during pregnancy. The placenta isn’t a wall. It’s a smart, selective gatekeeper. Sometimes it blocks harmful substances. Other times, it lets drugs slip through easily-sometimes with serious consequences.

The Placenta Is Not a Shield

For decades, people believed the placenta acted like a filter, keeping drugs and toxins away from the fetus. That idea was shattered in the late 1950s when thousands of babies were born with severe limb deformities after their mothers took thalidomide for morning sickness. The drug didn’t just pass through-it caused irreversible damage. Since then, we’ve learned the placenta doesn’t stop drugs. It just decides which ones get through-and how. At full term, the placenta weighs about half a kilogram, covers an area larger than a yoga mat, and has millions of tiny structures designed for exchange. It’s not passive. It’s alive, changing, and full of transport systems that actively push some drugs back toward the mother while letting others flow freely to the baby.How Drugs Actually Get Through

Not all drugs cross the placenta the same way. The main routes are simple physics and complex biology working together. Passive diffusion is the most common. Small, fat-soluble molecules slip easily through cell membranes. Alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine are perfect examples. They move quickly from mother to baby, often reaching nearly the same concentration in fetal blood as in the mother’s. That’s why drinking while pregnant puts the baby at direct risk. Larger molecules like insulin (over 5,800 Daltons) barely cross. The placenta physically blocks them. But size isn’t everything. A drug’s lipid solubility matters more. If it dissolves in fat, it slips through more easily. Drugs with a log P value above 2 cross 50-60% more readily than those below it. Ionization plays a big role too. At the body’s normal pH (7.4), drugs that are charged (ionized) struggle to pass. For example, many antibiotics become ionized and stay mostly on the mother’s side. But if the drug is neutral, it moves freely. Then there are the transporters. The placenta has built-in pumps-like P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and BCRP-that act like bouncers. They recognize certain drugs and shove them back into the mother’s circulation. This is why HIV medications like lopinavir and saquinavir show very low fetal exposure: up to 90% gets pumped back. But if you block these pumps-with another drug or a genetic variation-the baby gets more.What Happens When Drugs Cross?

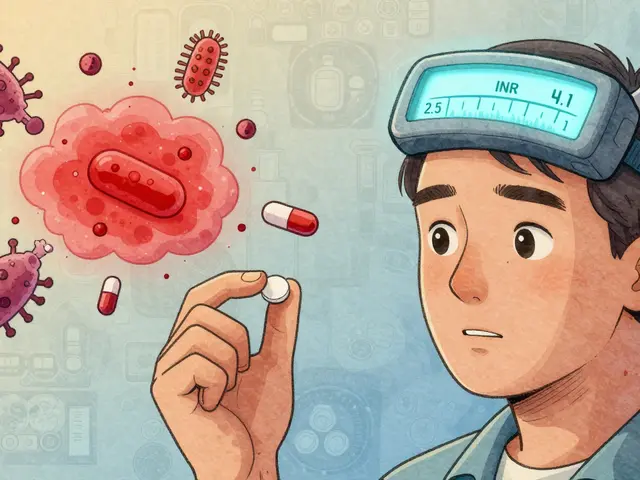

Just because a drug reaches the fetus doesn’t mean it’s harmless. The baby’s body is still growing. Organs are forming. Detox systems are immature. Even a small dose can have a big impact. SSRIs like sertraline cross easily-cord-to-maternal ratios of 0.8 to 1.0 mean the baby gets almost as much as the mother. Around 30% of babies exposed to these drugs in late pregnancy develop transient symptoms: jitteriness, breathing trouble, feeding issues. It’s not permanent, but it’s real. Opioids like methadone and buprenorphine cross with high efficiency. Fetal concentrations reach 65-75% of maternal levels. This leads to neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) in 60-80% of exposed newborns. These babies go through withdrawal-tremors, high-pitched crying, seizures. It’s not just a medical issue. It’s a social one, too. Antiseizure drugs like valproic acid cross almost completely. Studies show up to 11% of babies exposed to valproate develop major birth defects-heart problems, cleft palate, neural tube defects. That’s 5 times higher than the general population. Even phenobarbital, a decades-old drug, reaches full fetal levels and can cause long-term cognitive delays. Chemotherapy drugs are especially tricky. Paclitaxel crosses in about 25-30% of cases. That’s enough to harm a rapidly dividing fetus. But if P-gp is inhibited-say, by another medication-the transfer jumps to nearly 50%. That’s why cancer treatment during pregnancy requires extreme precision.

Timing Matters More Than You Think

The stage of pregnancy changes everything. The placenta isn’t the same at 8 weeks as it is at 38 weeks. In the first trimester, the barrier is looser. Tight junctions between cells aren’t fully formed. Efflux pumps like P-gp are still developing. This means small, dangerous drugs-like isotretinoin (for acne) or thalidomide-can slip through more easily. That’s why this is the most vulnerable window for birth defects. By the third trimester, the placenta becomes more protective. Transporters ramp up. But that doesn’t mean it’s safe. Drugs that accumulate over time-like lithium or certain antidepressants-can still build up in the fetus. And because the baby’s liver and kidneys are still immature, they can’t clear these drugs well.What About Protein Binding?

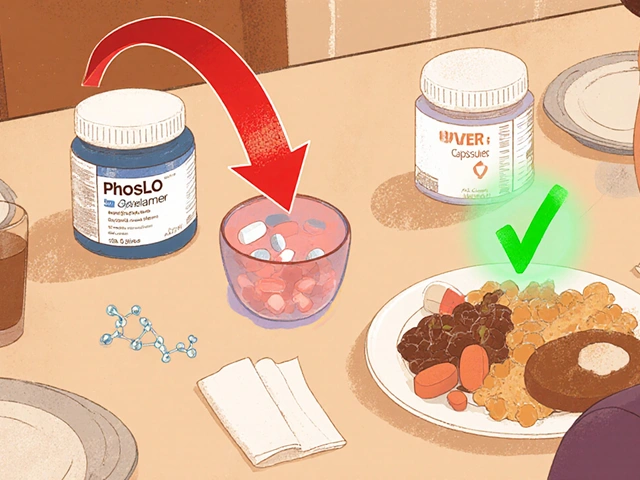

Only the unbound, or “free,” part of a drug can cross the placenta. If a drug is tightly stuck to proteins in the mother’s blood, it won’t make it through. Warfarin, for example, is 99% protein-bound. So even though it’s small and fat-soluble, very little reaches the baby. That’s why it’s sometimes used in pregnancy when blood thinners are needed. But even then, the tiny fraction that does cross can cause fetal warfarin syndrome-nasal hypoplasia, bone abnormalities. That’s why doctors check not just the dose, but also the free drug concentration in high-risk cases. For drugs like digoxin, which has a narrow safety window, monitoring levels in both mother and baby is standard practice.Why Animal Studies Don’t Tell the Whole Story

Most drug safety data comes from testing on rats and mice. But their placentas are very different. In mice, the barrier is thinner, the surface area is larger, and transporters work differently. A drug that seems safe in mice might be dangerous in humans-and vice versa. Studies show some drugs cross mouse placentas 3-4 times faster than human ones. That’s why the FDA and EMA now require human placental tissue studies before approving drugs for use in pregnancy. Dually perfused human placenta models-where a donated placenta is kept alive in a lab and drugs are pumped through-are becoming the gold standard. Even newer tools like placenta-on-a-chip are helping. These tiny devices mimic placental structure and function with surprising accuracy. One study showed glyburide (a diabetes drug) transfer rates in the chip matched real tissue within 1%. That’s a breakthrough.

Regulation and the Missing Data

In 2015, the FDA changed how drug labels describe pregnancy risks. No longer do they just say “Category C.” Now they must include specific data on placental transfer, fetal exposure, and known effects. But here’s the problem: 45% of prescription drugs still lack adequate pregnancy safety data. Why? Because testing on pregnant people is ethically complex. And until recently, drug companies didn’t prioritize it. The thalidomide disaster led to the Kefauver-Harris Amendment in 1962, which forced drug makers to prove safety. But even today, most new drugs aren’t tested in pregnant women until after they’re on the market. That means doctors are often guessing.What’s Next?

Scientists are now trying to do the opposite: not just block drugs from crossing, but target them. Imagine delivering a drug directly to the fetus to treat a genetic disorder-like sickle cell disease or congenital hypothyroidism-without affecting the mother. Nanoparticles are being tested for this. But there’s a catch: they might get stuck in the placenta, causing inflammation or damage. Early trials of P-gp modulators to enhance fetal drug delivery are set to begin in late 2024. If they work, they could revolutionize fetal medicine. But safety must come first.What Should You Do?

If you’re pregnant-or planning to be-don’t stop or start any medication without talking to your doctor. Even “safe” over-the-counter drugs like ibuprofen or cold medicines can have hidden risks. Ask:- Is this drug known to cross the placenta?

- What’s the evidence for fetal harm?

- Are there safer alternatives?

- Should I get my drug levels checked?

Can medications cause birth defects even if they cross the placenta in small amounts?

Yes. Even tiny amounts of certain drugs can disrupt fetal development, especially during the first trimester when organs are forming. For example, valproic acid causes major birth defects in up to 11% of exposed pregnancies-even though it crosses the placenta at only 90-100% efficiency. The fetus’s developing systems are extremely sensitive. A drug that’s harmless to an adult can be toxic to a fetus at much lower doses.

Do all antidepressants cross the placenta equally?

No. SSRIs like sertraline and citalopram cross easily, with cord-to-maternal ratios near 1.0. Others, like paroxetine, have slightly lower transfer rates. SNRIs like venlafaxine cross moderately. Some newer antidepressants, like vortioxetine, have limited data, but early studies suggest moderate transfer. The key isn’t just whether they cross-it’s how the baby’s brain responds to them after birth.

Is it safe to take ibuprofen during pregnancy?

It’s not recommended after 20 weeks. Ibuprofen crosses the placenta easily and can reduce amniotic fluid, affect fetal kidney development, and cause premature closure of a critical blood vessel in the baby’s heart. Before 20 weeks, occasional use under medical supervision may be acceptable, but acetaminophen is generally preferred for pain relief during pregnancy.

Why do some drugs like digoxin cross the placenta even though they’re large?

Digoxin is an exception. Even though it’s relatively large (780 Da), it uses specific transporters in the placenta that actively pull it into fetal circulation. Unlike drugs blocked by P-gp, digoxin isn’t pumped back. That’s why its fetal levels are close to maternal levels, even though it doesn’t fit the typical size rule. This is why therapeutic drug monitoring is essential when digoxin is used in pregnancy.

Can a mother’s diet or health affect how drugs cross the placenta?

Absolutely. Conditions like preeclampsia, diabetes, or infection can change placental structure and transporter function. Inflammation can reduce P-gp activity, letting more drugs through. Poor nutrition can lower protein levels, increasing the amount of free, unbound drug available to cross. Even smoking alters placental blood flow and increases permeability to nicotine and other toxins.

Are herbal supplements safe during pregnancy?

Many are not. Herbal products like black cohosh, dong quai, or pennyroyal can cross the placenta and trigger contractions or affect fetal hormones. Unlike prescription drugs, they aren’t tested for fetal safety. Just because something is “natural” doesn’t mean it’s safe. Always check with your provider before using any supplement.

How do scientists measure how much of a drug reaches the fetus?

The most accurate method is using a dually perfused human placenta model, where both maternal and fetal sides of a donated placenta are kept alive in a lab and drug concentrations are measured over time. Cord blood samples taken at birth also give real-world data. Ratios like cord-to-maternal concentration are calculated to show transfer efficiency. Newer techniques, like 11C-radioactive tracers and placenta-on-a-chip devices, are improving accuracy and reducing the need for human tissue samples.

Understanding how drugs move through the placenta isn’t just academic. It’s the difference between a healthy birth and a preventable tragedy. With better science, clearer labeling, and informed choices, we can protect both mother and baby-not by avoiding all medications, but by using them wisely.

Nicole M

12 Nov 2025 at 11:40I still can't believe how many people think the placenta is some kind of force field. It's not a filter-it's a bouncer with a whitelist. If a drug fits the profile-small, fat-soluble, neutral-it's in. No questions asked. Alcohol? Check. Nicotine? Check. Caffeine? Double check. And yet we act surprised when babies have issues. We're not protecting them-we're just lucky some drugs happen to be too big to sneak through.