When you hear the term mandatory substitution, you might think of swapping one drug for another at the pharmacy. But in global law, it’s far more complex-and it’s changing how governments regulate finance, mental health, and chemicals. Across countries, the same phrase means wildly different things depending on the system it’s embedded in. And the consequences? They ripple through banks, hospitals, and factories.

Banking: The EU’s Rule That Forced Institutions to Rewrite Risk Models

In Europe, mandatory substitution isn’t about people-it’s about money. Under Article 403(1) of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), banks must replace their exposure to the original borrower in certain repurchase agreements with exposure to the tri-party agent managing the deal. This rule, effective since June 2021, was meant to reduce systemic risk by centralizing accountability. But it didn’t come without friction. The European Banking Authority (EBA) required banks to implement strict reporting and verification systems. J.P. Morgan reported a 15-20% spike in operational costs just to comply. Mid-sized banks spent an average of €1.2 million upgrading their tech infrastructure. The goal was simple: if a bank lends against collateral, and a third party manages that collateral, then the bank’s risk should be tied to the agent-not the original issuer. But the U.S. took a different path. The Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC rejected mandatory substitution in their 2018 large exposure proposal. They argued internal risk models were more accurate than standardized rules. That created a clear divide: EU banks had to follow the rule. U.S. banks could opt out. The result? A regulatory gap that financial firms exploited. Twenty-two percent of EU-based institutions moved some repo operations to London after Brexit to avoid the stricter EU requirements. The Basel Committee’s 2023 update kept substitution optional globally, deepening the transatlantic split. And while the IMF claims mandatory substitution lowered systemic risk by 18%, the Bank for International Settlements found it increased operational risk by 12%. There’s no clear winner-just trade-offs.Mental Health: When the Law Appoints Someone to Decide for You

In mental health law, mandatory substitution means someone else-often a family member or court-appointed guardian-makes decisions for a person deemed incapable of doing so themselves. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening in hospitals, courts, and care homes across the world. Canada, Australia, England and Wales, and Northern Ireland all have frameworks allowing this. Ontario’s Substitute Decisions Act (1992) gives family members legal authority to make health and financial choices. England and Wales use the Mental Capacity Act (2005), which allows courts to appoint deputies. Northern Ireland followed with its own version in 2016. Victoria, Australia, uses the Guardianship and Administration Act (2019). But here’s the twist: the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), ratified by 182 countries, says this is a violation of human rights. Article 12 insists that people with disabilities must have equal recognition before the law-including the right to make their own choices, even if others disagree. The CRPD Committee’s 2014 General Comment declared substitute decision-making incompatible with human rights. This created a legal earthquake. Countries like Canada and Australia signed the CRPD but kept interpretive declarations that allowed substitute decision-making to continue. Meanwhile, Ontario has quietly shifted toward supported decision-making-helping people make their own choices with assistance. Since 2015, coercive interventions have dropped 12% in Ontario. But frontline workers say it’s hard to apply when someone has severe cognitive impairment. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s moving. The UK’s 2023 Mental Health Act reform proposes cutting compulsory interventions by 30% through better supported decision-making. But full rollout is delayed until 2026. Only 37 countries have fully aligned their laws with the CRPD. The rest? They’re still stuck between tradition and human rights.

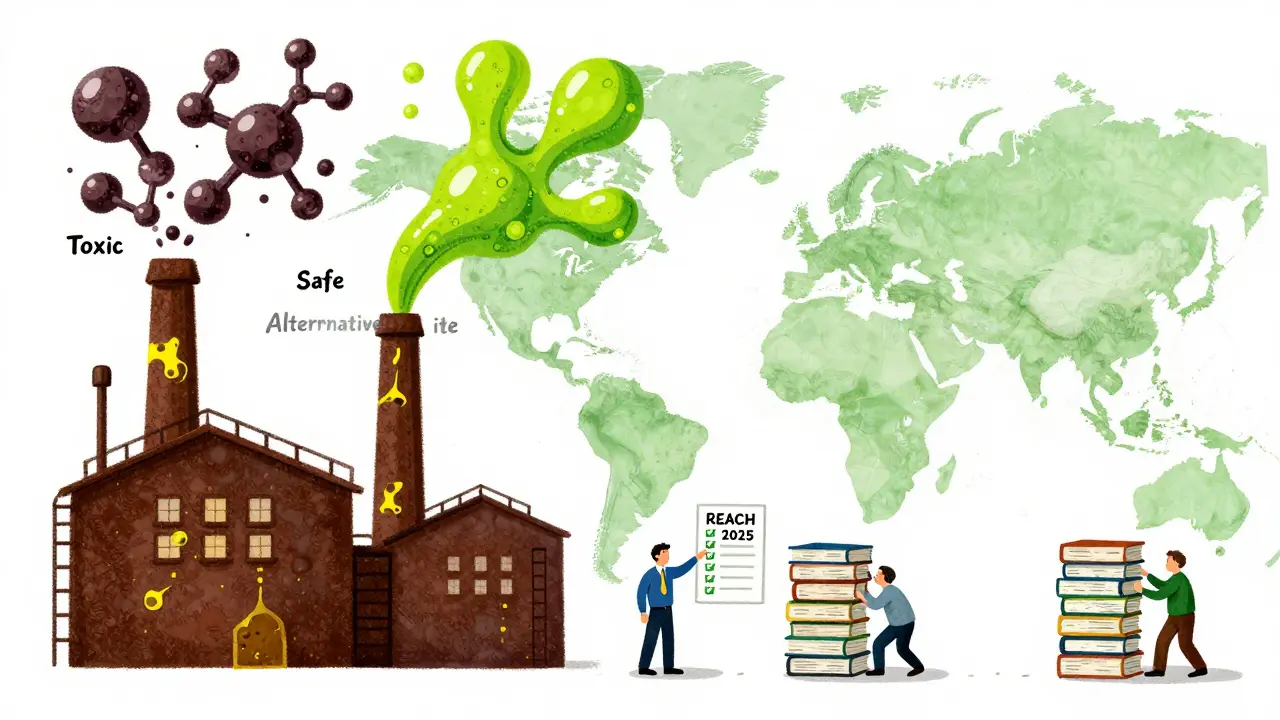

Chemicals: The EU’s Push to Replace Dangerous Substances

In environmental regulation, mandatory substitution means forcing companies to find safer alternatives to toxic chemicals. The EU’s REACH framework is the most aggressive in the world. If a substance is classified as “of very high concern”-like certain flame retardants, phthalates, or endocrine disruptors-manufacturers must apply for authorization to keep using it. And to get that authorization, they must prove they’ve tried to substitute it with something less harmful. BASF, one of the world’s largest chemical companies, reduced its use of these dangerous substances by 23% between 2016 and 2020. But small businesses struggled. SMEs reported average compliance costs of €47,000 per authorization application. ECHA, the EU’s chemicals agency, rejected 62% of initial applications because companies didn’t properly assess alternatives. The EU’s 2022 Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability took it further: by 2025, substitution planning will be mandatory for all restricted substances, not just authorized ones. That’s a big jump. Sweden’s PRIO list and ChemSec’s SIN List already acted as early-warning systems, but now the EU is turning them into legal requirements. The global market for safer chemical alternatives is now worth $14.3 billion. Seventy-three percent of chemical manufacturers say they’ve increased R&D spending since 2016. But critics point out: without clear definitions of what counts as a “suitable alternative,” companies are left guessing. Some just repackage the same chemicals under new names.

Why the Same Term Means Different Things

You might wonder: why does “mandatory substitution” mean one thing in banking, another in mental health, and something else in chemicals? Because each system was built for a different purpose. In finance, it’s about risk control. In mental health, it’s about protection-sometimes paternalistic, sometimes necessary. In chemicals, it’s about prevention and innovation. The real challenge isn’t the rule itself. It’s the lack of global alignment. The U.S. doesn’t force banks to substitute. The UK still allows guardians to override patient autonomy. China, India, and Brazil don’t have REACH-style rules at all. This creates a patchwork where companies must tailor products, services, and policies for each jurisdiction. It also means compliance is expensive. Financial firms spent years rewriting systems. Mental health services needed new training programs. Chemical companies hired toxicologists and legal teams just to keep up.What’s Next? The Tension Between Control and Rights

Looking ahead, the pressure will only grow. In finance, regulators are testing AI-driven risk models that could eventually replace manual substitution rules. In mental health, countries like Ireland and New Zealand are piloting supported decision-making courts. In chemicals, the EU is pushing for global recognition of its SIN List as a benchmark. But progress is uneven. Experts predict 78% of financial regulators will move toward more harmonized rules by 2030. Yet 63% believe mental health laws will keep clashing with the CRPD until at least 2035. The core question remains: who gets to decide? The bank? The court? The regulator? Or the person affected? There’s no universal answer. But one thing is clear: mandatory substitution isn’t just a legal technicality. It’s a mirror of society’s values-about risk, autonomy, safety, and justice.Is mandatory substitution the same as forced treatment in mental health?

Yes, in mental health law, mandatory substitution refers to situations where a court or family member is legally authorized to make decisions for someone who is deemed unable to do so themselves. This is often called substitute decision-making. It’s used in cases of severe mental illness or cognitive impairment. But under the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, this practice is increasingly seen as a violation of autonomy. Many countries are now shifting toward supported decision-making, where individuals receive help making their own choices rather than having others decide for them.

Why does the EU require mandatory substitution in banking but the U.S. doesn’t?

The EU adopted mandatory substitution under the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) to standardize risk exposure in tri-party repo markets and reduce systemic instability. The U.S. regulators, including the Federal Reserve and OCC, rejected it because they believe internal risk models used by large banks are more accurate and flexible. The U.S. prefers a principles-based approach, while the EU leans toward rules-based enforcement. This difference created a regulatory arbitrage opportunity, with some EU banks shifting operations to London after Brexit to avoid the stricter EU rules.

How does REACH’s substitution rule affect small businesses?

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face significant challenges under REACH’s substitution requirements. The average cost of one authorization application is €47,000, and many lack the in-house toxicology expertise needed to prove alternatives are safe and feasible. ECHA rejected 62% of initial applications due to inadequate alternatives assessments. This has forced many SMEs to either exit the EU market, outsource compliance, or raise prices. Some have partnered with industry groups to share research on safer substitutes, but progress is slow.

Can a person refuse substitute decision-making in mental health?

In most jurisdictions, if a court has already appointed a substitute decision-maker, the individual’s objections don’t automatically override the order. However, in places like Ontario and Victoria, the law now requires that the person’s wishes and preferences be considered in every decision. The CRPD pushes for full autonomy, but legal systems haven’t fully caught up. Some countries, like Ireland and New Zealand, are testing new court models that prioritize supported decision-making over forced substitution, but these are still exceptions.

Are there global standards for mandatory substitution?

No. Each domain-finance, mental health, chemicals-has its own international norms, but no unified global standard exists. The Basel Committee allows optional substitution in banking. The UN CRPD opposes substitute decision-making in mental health. The EU’s REACH mandates substitution in chemicals. Other countries follow or ignore these based on their legal traditions. This lack of alignment forces multinational companies to maintain multiple compliance systems, increasing costs and complexity.

What’s the difference between mandatory substitution and voluntary substitution?

Mandatory substitution is legally required-failure to comply results in fines, loss of license, or legal liability. Voluntary substitution is a business or policy choice, often driven by sustainability goals or customer demand. For example, a chemical company might voluntarily remove a toxic ingredient to improve its brand image, even if the law doesn’t require it. In banking, voluntary substitution might mean a bank chooses to simplify its exposure structure even if not forced to. Only in the EU’s CRR and REACH frameworks is substitution truly mandatory.

Jocelyn Lachapelle

16 Dec 2025 at 19:00This is the kind of deep dive we need more of. Mandatory substitution isn't just policy-it's a mirror of what we value. Risk control vs. human dignity vs. environmental survival. No wonder the world feels so fractured.