When a doctor writes a prescription for a drug like warfarin, levothyroxine, or tacrolimus, they’re not just picking a medicine-they’re managing a tightrope walk. These are Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs, where even a small change in dose can mean the difference between healing and harm. A blood level just 10% too high might cause bleeding; 5% too low could lead to a clot, transplant rejection, or seizure. And yet, pharmacists across the U.S. are legally allowed to swap brand-name versions for generics without telling the doctor-unless state law says otherwise.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

An NTI drug is defined by its razor-thin safety margin. The FDA says it’s any drug where the gap between the lowest effective dose and the lowest toxic dose is two or less. That’s not just tight-it’s precarious. For comparison, most medications have a ratio of 10 or higher. Warfarin, for example, has a ratio of 1.5. A patient taking 5 mg daily might need 4.8 mg one week and 5.2 mg the next, depending on diet, other meds, or even genetics. Switching brands-even if both are FDA-approved-can nudge that level out of range.

The FDA tightened its rules in 2019. For regular generics, bioequivalence is accepted if blood levels fall between 80% and 125% of the brand. For NTI drugs, that range shrinks to 90%-111%. That sounds strict, but many doctors still don’t trust it. Why? Because those tests are done on healthy volunteers, not patients with liver disease, kidney failure, or multiple chronic conditions. A 2020 FDA report claimed 98% of NTI generics perform within 3-4% of the brand, but transplant surgeons and neurologists have seen otherwise.

Doctors Are Divided-And It’s Not Just About Cost

Most prescribers know generics save money. But with NTI drugs, cost isn’t the only factor. A 2023 survey by the American College of Physicians found that 57% of internists would choose the brand-name version when starting a high-risk patient on an NTI drug. Their top reason? Stability. Not fear of generics. Not distrust of science. Just the fact that once a patient is stable on one version, changing it-even to an FDA-approved generic-can disrupt everything.

Psychiatrists managing lithium for bipolar disorder report the most disruption. One in three saw patients return with tremors, confusion, or kidney issues after a switch. Primary care doctors see fewer dramatic cases, but still report 29% more office visits after substitutions, according to MGMA data. Each visit costs an estimated $127 in time, labs, and administrative work. And patients? They get confused. One woman told her doctor she was "feeling off" after her pharmacist switched her levothyroxine. She didn’t know it was the same drug. She thought she’d been given the wrong pill.

Pharmacists Are Doing Their Job-But the System Doesn’t Help

Pharmacists aren’t the problem. In fact, 82% of them almost always substitute generics for new NTI prescriptions, and 94% believe doctors think generics are just as safe. But here’s the catch: only 60% do the same for refills. Why? Because they know doctors don’t like it. Many pharmacists quietly avoid substitutions for warfarin or tacrolimus unless they’re asked. Others notify the prescriber by phone or email. A 2021 survey found 78% of hospital pharmacists always inform the doctor before swapping an NTI drug.

But notification isn’t standardized. Some doctors get emails. Others get faxes. A few still get handwritten notes. And 63% of physicians say they’d prefer electronic alerts over phone calls. Right now, there’s no national system to flag an NTI substitution in the EHR. No alert pops up. No flag appears in the patient’s chart. The change just shows up as a new prescription line-barely noticeable.

State Laws Are a Patchwork-And They Matter

Twenty-eight states have laws that affect how NTI drugs can be substituted. Some require the pharmacist to get the doctor’s permission. Others require the patient to sign a form. Seventeen states have "affirmative consent" laws, meaning the patient must agree before the switch. In those states, generic substitution rates for NTI drugs are 23% lower than in states with no restrictions.

Texas and Florida keep official NTI lists. If a drug is on the list, substitution is blocked unless the prescriber writes "Do Not Substitute" or initials the prescription. Other states leave it up to the pharmacist’s judgment. The result? A patient in Georgia might get a generic without a second thought. The same patient in New York might get the brand-just because of where they live.

Who’s Saying What-and Why?

The American Medical Association (AMA) says substitution is fine for most patients. They’ve held this position since 2007, arguing that therapeutic drug monitoring makes the switch safe. But they also admit that for some drugs-like phenytoin or lithium-doctors should be involved. The American Academy of Neurology disagrees. They explicitly say automatic substitution for levothyroxine, phenytoin, and warfarin is inappropriate without prescriber input.

The FDA stands by its data. They say post-market surveillance shows NTI generics perform nearly identically to brands. But the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) found over 1,200 medication errors linked to NTI substitutions between 2015 and 2020. Eight percent caused harm. That’s not a lot-but it’s not zero. And for the families who lost a loved one to a missed INR or a rejected transplant, it’s everything.

Meanwhile, the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy opposes laws that restrict substitution, arguing pharmacists should use professional judgment. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists disagrees. They want mandatory notification. The debate isn’t about science-it’s about who controls the process.

What’s Changing? And What’s Next?

The FDA added 12 new drugs to the NTI list in March 2023 and removed three. That’s not just administrative-it’s a signal that they’re listening. The PRESCRIPT-NTI trial, currently tracking 1,200 patients across 42 hospitals, is expected to release data in early 2024. It’s the first large-scale study to measure actual clinical outcomes after substitution.

Medicare is also moving. In November 2023, CMS proposed a rule requiring prescriber notification for all NTI substitutions under Part D. That could force EHR vendors to build alerts. It could mean fewer phone calls, more automated flags, and better tracking.

Market data shows doctors still prefer brands. Tacrolimus has a 32% brand-name retention rate. Warfarin? 28%. Even though generics cost 80% less, patients and doctors keep going back to the original. Why? Because trust isn’t built in labs-it’s built in clinics, in conversations, in outcomes.

What Should Prescribers Do?

If you prescribe NTI drugs, here’s what works:

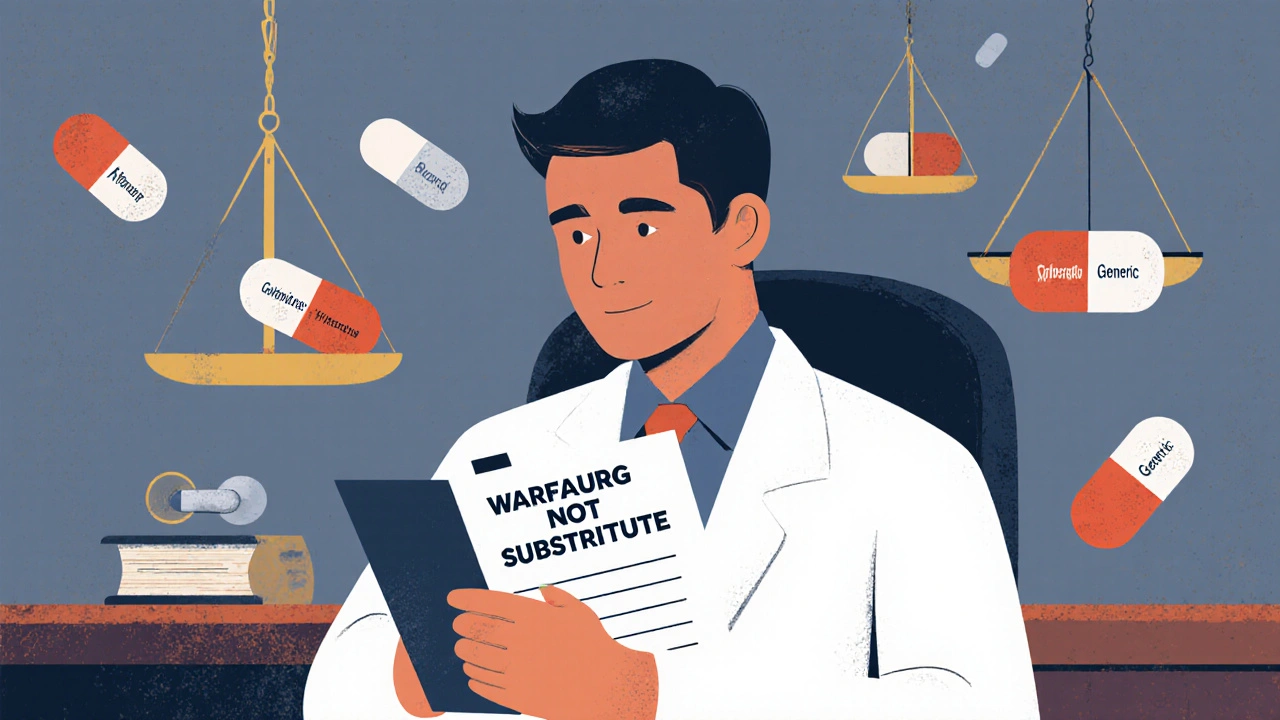

- Write "Do Not Substitute" on the prescription if you’re unsure. It’s simple. It’s legal. It’s clear.

- Use electronic prescribing. Many EHRs let you flag NTI drugs. Use it.

- Talk to your patients. Tell them: "This medicine is very sensitive. Don’t let your pharmacist switch it without checking with me first."

- Monitor closely. Check blood levels after any switch-no matter what the label says.

- Know your state’s rules. If your state requires consent, make sure your staff knows how to handle it.

There’s no perfect answer. Generics save billions. But for patients on NTI drugs, stability isn’t a luxury-it’s a lifeline. The science says substitution is safe. The experience says it’s risky. Until we have real-time data, clear communication, and national standards, the safest choice is often the one that doesn’t change at all.

Are generic NTI drugs really as safe as brand-name ones?

The FDA says yes, based on bioequivalence testing and post-market data showing 98% of NTI generics perform within 3-4% of the brand. But real-world evidence tells a different story. Doctors treating transplant, psychiatric, and neurology patients report more instability after switches. The difference isn’t in the lab-it’s in the patient. A healthy volunteer’s blood level doesn’t reflect someone on six other drugs, with kidney disease or fluctuating diet. For many, stability matters more than equivalence.

Can a pharmacist substitute an NTI drug without telling the doctor?

In most states, yes. Only 17 states require patient consent before substitution, and only 28 have any NTI-specific rules. In states without restrictions, pharmacists can swap generics without notifying the prescriber. That’s why many doctors now write "Do Not Substitute" on prescriptions or use electronic flags to block automatic swaps.

Which NTI drugs are most likely to cause problems after substitution?

The top five NTI drugs linked to substitution issues are warfarin (blood thinner), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), phenytoin (seizure control), lithium (mood stabilizer), and tacrolimus (transplant immunosuppressant). These have narrow margins, complex metabolism, and are sensitive to small changes. Even minor shifts in blood levels can lead to bleeding, thyroid dysfunction, seizures, toxicity, or organ rejection.

Why do some doctors still prescribe brand-name NTI drugs?

Because once a patient is stable on a specific version, changing it-even to an FDA-approved generic-can throw off their balance. Studies show 73% of internists cite stability concerns as their main reason. It’s not about distrust of generics. It’s about avoiding disruption. For patients on chronic therapy, consistency matters more than cost. A 2022 Medicare report showed brand-name NTI drugs held 23% market share, far higher than non-NTI drugs.

What’s the best way to reduce NTI substitution errors?

Three things: First, write "Do Not Substitute" on prescriptions. Second, use electronic prescribing with NTI flags. Third, educate patients: tell them not to accept a switch without checking with you. Add monitoring-check INR, TSH, or drug levels after any substitution. The goal isn’t to block generics. It’s to make sure any change is intentional, tracked, and safe.

Travis Freeman

28 Nov 2025 at 18:25Really appreciate this breakdown. I’ve seen patients panic when their pill looks different, even when it’s the same active ingredient. A little education goes a long way-telling folks "this isn’t a new drug, just a different maker" can ease so much anxiety.