Children don’t always tell you when they’re struggling to see. A kid might squint at the TV, sit too close to the screen, or rub their eyes constantly-but they won’t say, "I can’t see clearly." That’s why pediatric vision screening isn’t just a checkmark on a doctor’s list. It’s a critical window to catch problems before they become permanent.

Why Screening Before Age 5 Matters

The human eye keeps developing until about age 7. After that, the brain stops adapting to blurry signals. If a child has amblyopia (lazy eye) or strabismus (crossed or turned eyes) and it’s not caught early, treatment becomes much harder. Studies show that when amblyopia is treated before age 5, 80-95% of kids regain normal vision. After age 8, that number drops to just 10-50%. That’s not a small difference-it’s the difference between seeing clearly for life or living with permanent vision loss.Amblyopia affects 1.2% to 3.6% of all children. Strabismus affects nearly 2% to 3.4%. That means in a classroom of 30 kids, at least one likely has a vision problem no one has noticed. These aren’t rare conditions. They’re common, silent, and treatable-if caught early.

How Vision Screening Works by Age

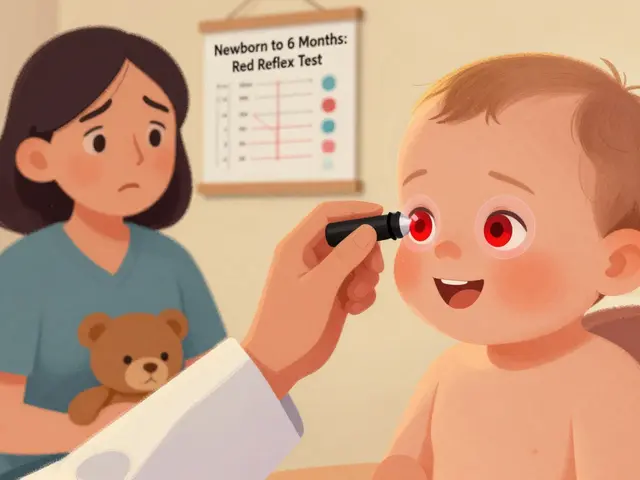

Screening isn’t one-size-fits-all. It changes as kids grow.For infants (newborn to 6 months): The red reflex test is the standard. A doctor shines a light into each eye and looks for a red glow in the pupil. If one eye looks darker or white, it could mean cataracts, retinal issues, or tumors. This simple test takes seconds but can catch life-altering problems before a baby even smiles.

From 6 months to 3 years: Doctors check eye alignment, pupil response, and how the eyes track movement. They also repeat the red reflex. No eye chart yet-kids this young can’t point to letters. But they can follow a toy or react to light. If an eye turns in or out consistently, that’s a red flag.

Age 3 and older: This is when visual acuity testing begins. Kids are asked to identify symbols or letters from 10 feet away. The most common charts use LEA symbols (apple, house, circle, square) or HOTV letters (H, O, T, V). These are easier for young kids than traditional Snellen letters.

The pass/fail lines are strict:

- Age 3: Must read the 20/50 line

- Age 4: Must read the 20/40 line

- Age 5+: Must read the 20/32 line (or 20/30 on Snellen)

If a child can’t hit the right line, they’re referred to a pediatric eye specialist. No waiting. No "just watch and see." Early referral means early treatment-and better outcomes.

Two Main Methods: Charts vs. Machines

There are two ways to screen: traditional eye charts and instrument-based devices.Eye chart screening is the gold standard for kids who can cooperate. It’s low-cost, widely available, and doesn’t need fancy equipment. But it has limits. About 10-25% of 3- and 4-year-olds just won’t play along. They get distracted. They’re shy. They don’t understand the game. That’s not their fault-it’s developmentally normal.

Instrument-based screening uses devices like the SureSight, Power Refractor, or the newer blinq™ scanner. These machines shine light into the eye and measure how it focuses, all in 1-2 minutes. No child response needed. The blinq™ scanner, cleared by the FDA in 2018, detected referral-worthy conditions with 100% sensitivity and 91% specificity in children aged 2-8. That means it rarely misses a real problem-and doesn’t overcall harmless ones.

But here’s the catch: instruments can flag kids with small refractive errors that don’t need glasses. That leads to false positives. So they’re best used as a first filter, especially for kids who won’t sit still for an eye chart. Experts agree: for kids aged 3-5, instrument screening is becoming the standard of care. For kids 5 and older who can read, charts still win.

Who Should Be Screened and When

Guidelines are clear and backed by decades of research:- The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends at least one screening between ages 3 and 5.

- The American Academy of Pediatrics says screening should happen at 8, 10, 12, and 15 years-but also supports instrument screening starting at age 1.

- State Medicaid programs in 47 states require vision screening as part of well-child visits.

That means most kids in the U.S. get screened during routine checkups. But not all. A 2019 National Survey of Children’s Health found Hispanic and Black children were 20-30% less likely to get screened than white children. That’s a gap that needs closing. Vision problems don’t care about race or income. But access still does.

What Happens If Something’s Found

A failed screen doesn’t mean your child needs glasses. It means they need a full eye exam by a pediatric ophthalmologist or optometrist. Most of the time, the issue is:- A refractive error (nearsightedness, farsightedness, or astigmatism)

- Amblyopia (lazy eye)

- Strabismus (eye misalignment)

Treatment is often simple: glasses, patching the stronger eye for a few hours a day, or eye drops that blur the good eye to force the weak one to work. In some cases, surgery fixes eye muscle alignment. The key is speed. The sooner treatment starts, the better the vision recovery.

Left untreated, amblyopia can lead to lifelong vision loss in one eye. That means your child could lose depth perception, struggle with sports, or have trouble with jobs that require fine visual detail. It’s not just about seeing the board in school. It’s about their future.

Common Mistakes in Screening

Even with good guidelines, things go wrong:- Wrong distance: The chart must be 10 feet away. If it’s 8 feet, the child passes easier. If it’s 12 feet, they might fail unfairly.

- Poor lighting: If the room is too dim, the child can’t see the symbols. A 2018 study found 25% of screenings had bad lighting.

- Not testing each eye separately: Covering one eye at a time is crucial. Kids often use their better eye to guess.

- Using Snellen letters too early: Letters like E, F, P, and T are hard for 3-year-olds. LEA symbols and HOTV are designed for them.

Training helps. Healthcare providers need 2-4 hours of practice to do it right. Quarterly quality checks keep standards high.

The Bigger Picture

Vision screening isn’t expensive. A basic autorefractor costs $5,500-$8,500. That’s less than a single pediatrician’s salary for one month. And the return? The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found every dollar spent on screening saves $3.70 in future costs-lost productivity, special education, medical care for preventable blindness.It’s not just about eyes. It’s about learning. Kids with uncorrected vision problems are more likely to fall behind in school. They get labeled "inattentive" or "slow learners." But sometimes, they just can’t see the words.

The future is moving toward earlier screening. Research published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2022 showed instrument-based screening works reliably as early as 9 months. That’s likely to change guidelines by 2025. The goal? Catch problems before a child even starts preschool.

What Parents Should Do

You don’t need to be an expert. But you should know:- Ask for vision screening at every well-child visit starting at age 1.

- If your child squints, tilts their head, or closes one eye in bright light, don’t wait-get it checked.

- Even if they pass, watch for signs: frequent eye rubbing, headaches after reading, trouble recognizing faces.

- Don’t assume school screenings are enough. They’re often basic. A full pediatric screen is more thorough.

There’s no harm in being proactive. But there’s real risk in waiting.

Tasha Lake

8 Feb 2026 at 19:08Just read through this and wow-the stats on amblyopia recovery rates before age 5 are insane. 80-95% vs. 10-50% after 8? That’s not just a clinical difference, that’s a life trajectory shift. And the blinq™ scanner’s 100% sensitivity? Game changer for non-cooperative toddlers. We’re talking about neuroplasticity windows here-once the visual cortex stops adapting, you’re basically stuck with suboptimal wiring. This isn’t ‘get glasses’-this is preventing cortical suppression before it locks in. Parents need to know: if your kid won’t sit still for a chart, push for instrument-based screening. It’s not lazy-it’s evidence-based.

Also, why are we still using Snellen letters for 3-year-olds? LEA symbols and HOTV exist for a reason. It’s like asking a toddler to read Shakespeare before they know the alphabet.