When you hear Labetalol is a mixed alpha‑ and beta‑adrenergic blocker used to treat high blood pressure and certain heart conditions. It’s a go‑to drug for many clinicians because it lowers both heart rate and vascular resistance. But what happens when the same patient also has Liver disease - a condition that ranges from mild fatty liver to end‑stage cirrhosis? This article breaks down the pharmacology, the risks, and the practical steps you need to keep patients safe.

How Labetalol Works: A Quick Pharmacology Refresher

Labetalol blocks β1, β2 and α1 receptors. By doing so it reduces cardiac output (β‑blockade) and dilates peripheral vessels (α‑blockade). The combined effect drops systolic and diastolic pressure without a dramatic drop in heart rate, which is why it’s popular in hypertensive emergencies.

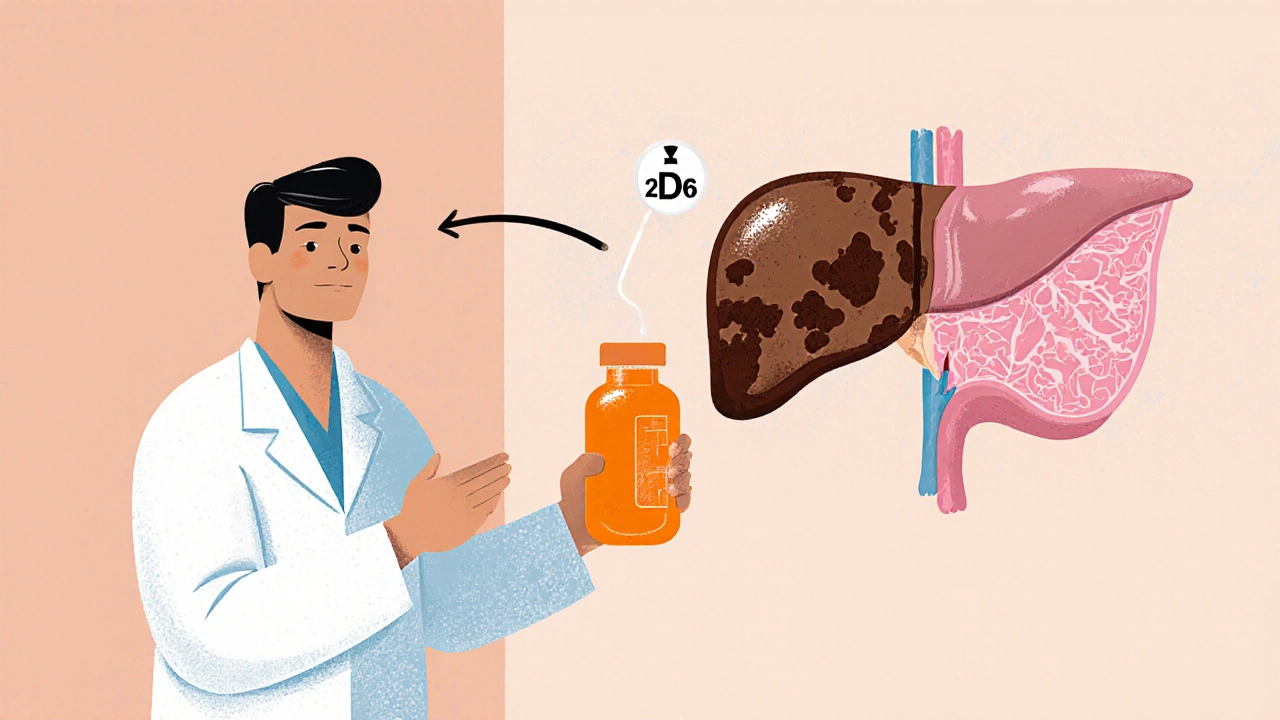

After oral administration, about 25 % of the dose reaches systemic circulation unchanged; the rest undergoes extensive first‑pass metabolism in the liver. The primary metabolic route involves the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2D6, converting labetalol to several inactive metabolites that are eliminated renally. Because the liver does the heavy lifting, any impairment can change drug levels dramatically.

Why Liver Disease Changes the Equation

In liver disease the following factors matter:

- Reduced enzymatic activity: Fibrosis and cirrhosis lower CYP2D6 function, slowing labetalol clearance.

- Altered protein binding: Hypoalbuminemia increases the free fraction of labetalol, amplifying its pharmacologic effect.

- Portosystemic shunting: Blood bypasses the liver, delivering more drug to the systemic circulation unchanged.

- Renal dysfunction: Many liver patients develop hepatorenal syndrome, further impairing excretion of metabolites.

These changes can push labetalol concentrations above the therapeutic window, raising the risk of bradycardia, hypotension, and even acute liver decompensation.

Clinical Evidence: What the Studies Show

Several small‑scale studies and case series have looked at labetalol in cirrhotic patients. A 2022 prospective cohort of 78 patients with Child‑Pugh class A‑B cirrhosis reported a 12 % incidence of symptomatic hypotension compared with 4 % in matched controls without liver disease. In a 2023 case‑report series of five patients with decompensated (Child‑Pugh C) cirrhosis, two required intensive‑care support after standard labetalol dosing, highlighting the need for dose reductions.

While large randomized trials are lacking, the consensus from hepatology societies (e.g., EASL 2021 guidelines) recommends starting at half the usual dose for moderate disease and considering alternative agents for severe disease.

Practical Dosing Recommendations

The table below summarizes commonly accepted dose adjustments based on the severity of liver disease. Values are rounded for bedside use and assume normal renal function; adjust further if creatinine clearance is <30 mL/min.

| Severity (Child‑Pugh) | Usual Oral Dose | Adjusted Oral Dose | Usual IV Loading | Adjusted IV Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class A (mild) | 100-200 mg BID | 75-150 mg BID | 20 mg over 2 min | 10-15 mg over 2 min |

| Class B (moderate) | 100-200 mg BID | 50-100 mg BID | 20 mg over 2 min | 5-10 mg over 2 min |

| Class C (severe) | Contraindicated or use only under specialist supervision |

Consider alternative beta‑blocker (e.g., carvedilol) or non‑pharmacologic control | Contraindicated | - |

Key take‑aways:

- Start low and go slow - a 25‑50 % dose reduction is a safe baseline for anyone beyond Child‑Pugh A.

- Monitor blood pressure and heart rate every 4-6 hours for the first 48 hours after initiation or dose change.

- Check liver function tests (ALT, AST, bilirubin) at baseline and weekly for the first month.

Monitoring and Managing Side Effects

Even with dose adjustments, labetalol can still cause problems.

- Hypotension: If systolic < 90 mmHg or MAP < 65 mmHg, reduce dose or hold the next dose. Give IV fluids cautiously in patients with ascites.

- Bradycardia: Heart rate < 50 bpm warrants dose reduction; consider atropine if symptomatic.

- Liver decompensation: Worsening encephalopathy, rising INR, or new ascites may signal that labetalol is contributing to hemodynamic stress.

- Bronchospasm: Though rare, beta‑blockade can trigger bronchoconstriction, especially in patients with underlying COPD.

Most issues are reversible with dose tweaks or temporary discontinuation. Always involve a hepatologist if decompensation appears.

Alternative Blood‑Pressure Strategies in Liver Disease

When labetalol isn’t ideal, clinicians have other options:

- Carvedilol: Another mixed α/β blocker with a slightly better safety profile in portal hypertension; however, it still undergoes hepatic metabolism.

- Nadolol or Propranolol: Pure β‑blockers that are less dependent on hepatic clearance; frequently used for variceal bleed prophylaxis.

- Calcium channel blockers (e.g., amlodipine): Non‑beta agents that bypass liver metabolism largely, though they can worsen peripheral edema.

- Lifestyle modification: Sodium restriction, weight management, and abstinence from alcohol remain foundational.

Choosing the right agent hinges on the primary indication (hypertension vs. portal hypertension) and the patient's liver function stage.

Patient Counseling Checklist

Clear communication can prevent many avoidable complications. Use this short checklist during the consultation:

- Explain why a lower dose is needed because the liver can’t break the drug down as usual.

- Instruct the patient to monitor for dizziness, fainting, or unusually slow heartbeat.

- Advise a daily log of blood pressure readings at home - aim for at least two measurements per day.

- Discuss signs of worsening liver disease (yellowing skin, increasing abdominal girth, confusion) and when to call the clinic.

- Confirm that the patient isn’t taking over‑the‑counter herbal supplements that can further strain liver enzymes (e.g., milk thistle at high doses).

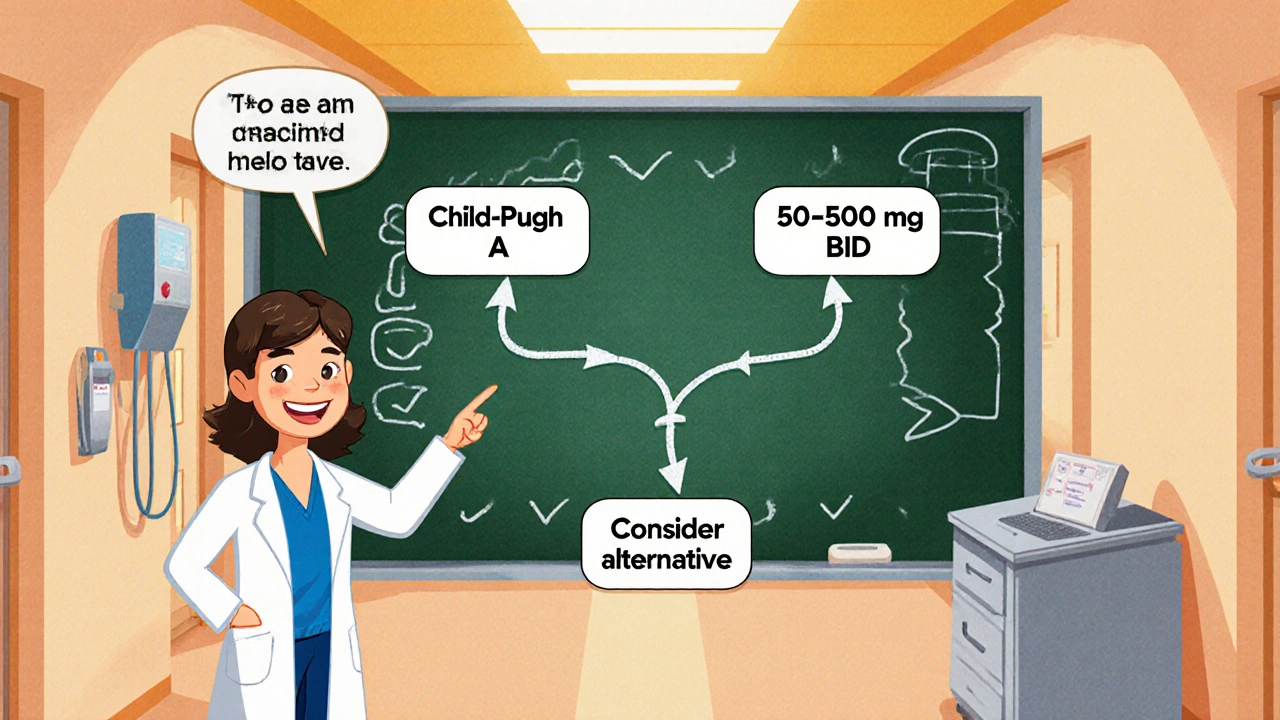

Quick Reference: Decision Tree for Clinicians

- Assess liver disease severity (Child‑Pugh score).

- Is the patient Child‑Pugh A?

- Yes - start at 75 % of usual dose, monitor.

- No - go to step 3.

- Is the patient Child‑Pugh B?

- Yes - start at 50 % of usual dose, monitor closely.

- No - go to step 4.

- Is the patient Child‑Pugh C?

- Yes - avoid labetalol; consider carvedilol or propranolol under specialist care.

This flowchart saves time and reduces dosing errors.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take labetalol if I have mild fatty liver?

Yes, but start with a 25 % dose reduction and watch your blood pressure closely. Fatty liver usually preserves enough CYP2D6 activity to handle standard doses, but the safety margin is still useful.

What’s the biggest red flag while on labetalol with cirrhosis?

A sudden drop in systolic pressure below 90 mmHg combined with worsening encephalopathy. That combo suggests the drug is compromising hepatic blood flow.

Is labetalol safe during pregnancy if the mother also has liver disease?

Pregnancy already raises the bar for drug safety. The lack of robust data means most obstetricians prefer alternatives like labetalol only when benefits clearly outweigh the potential hepatic risks.

How often should liver function tests be repeated after starting labetalol?

Check baseline labs, then repeat at 1‑week and 4‑week intervals. If any values rise more than 2‑fold, reconsider the regimen.

Can I switch from labetalol to propranolol without a washout period?

A short overlap (24‑48 hours) is advisable to avoid abrupt changes in heart rate and blood pressure. Taper labetalol while titrating propranolol up.

Bottom Line

In patients with any degree of liver disease, labetalol is not a “set‑and‑forget” medication. Adjust the dose according to Child‑Pugh class, monitor vitals and liver labs aggressively, and keep a low threshold for switching to an alternative agent. By respecting the liver’s role in drug metabolism, clinicians can harness labetalol’s benefits while keeping safety front‑and‑center.

Melody Barton

25 Oct 2025 at 17:41Great overview! If you're treating a patient with cirrhosis, start with half the usual labetalol dose and watch their blood pressure closely. It’s also a good idea to check liver function tests after the first 24‑hours.