Have you ever started a new medication and suddenly felt sick - even though the drug was supposed to help you? Maybe you got a headache, felt nauseous, or couldn’t sleep. Then you found out the pill you were taking was just a sugar pill in a clinical trial. That’s not a coincidence. It’s the nocebo effect.

Most people know about the placebo effect - when you feel better because you believe a treatment will work. But far fewer know about its darker twin: the nocebo effect. This is when you feel worse because you expect to. It doesn’t matter if the pill is real or fake. If you’re told it might cause dizziness, fatigue, or stomach pain, your brain can make those symptoms real. And it’s happening more often than you think.

What Exactly Is the Nocebo Effect?

The word nocebo comes from Latin, meaning "I will harm." It’s the flip side of placebo - which means "I will please." While a placebo can make you feel better just by believing in it, a nocebo can make you feel worse just by fearing it.

It’s not just "in your head." Brain scans show real changes. When someone expects pain or side effects, areas like the anterior cingulate cortex and insula light up - the same regions that activate during actual physical pain. Your body isn’t lying. It’s responding to your expectations like they’re facts.

In clinical trials, about 20% of people taking a sugar pill report side effects. Nearly 10% quit the trial because they felt unwell. And here’s the kicker: these people were never told they were on a fake drug. They just read the leaflet - and their brain did the rest.

How Does It Actually Happen?

The nocebo effect doesn’t come out of nowhere. It’s built from three main sources:

- What you’re told - If your doctor says, "This drug can cause severe nausea in some people," your brain starts scanning for nausea.

- What you read - Patient information leaflets list every possible side effect, even ones that happen in 1 in 10,000 cases. The longer the list, the more symptoms people report.

- What you’ve seen - If a friend had a bad reaction to a drug, or if a news story says "Generic version causes weird side effects," your brain takes that as a warning signal.

One study found that when patients were given a medication leaflet with 15 side effects listed, 42% reported at least one. When the same drug had a leaflet with only 5 side effects, only 18% reported any. The drug didn’t change. The list did.

And it’s not just about information. The way it’s delivered matters. Saying, "Most people don’t notice any difference," works better than saying, "Some people have bad reactions." Tone, body language, and even how long the doctor pauses before explaining side effects can shift how your brain interprets the risk.

Real-World Examples You’ve Probably Seen

In 2017, New Zealand switched patients from brand-name venlafaxine to a generic version. The active ingredient was identical. The dosage was the same. But after media coverage warned about "possible side effects," reports of nausea, dizziness, and anxiety jumped by over 300%. No new drug. Just new fear.

On Reddit, you’ll find hundreds of posts like this one: "I switched from brand-name sertraline to generic. I got insomnia and vomiting. My pharmacist said it was probably psychological. I went back to the brand - and the symptoms vanished."

PatientsLikeMe forums show the same pattern: people report side effects that match exactly what’s written in the leaflet - even if they never had those symptoms before. Your brain doesn’t just notice symptoms. It creates them.

Why Do Some People Get It More Than Others?

Not everyone is equally affected. Research shows certain groups are more vulnerable:

- Women - report 23% more side effects than men in placebo groups.

- People with anxiety or depression - are 1.7 times more likely to experience nocebo effects.

- Pessimistic thinkers - tend to focus on worst-case scenarios.

- People who’ve had bad medical experiences - their brains are primed to expect harm.

It’s not about being "weak-minded." It’s about how your brain has learned to protect you. If you’ve had a bad reaction before, your brain flags similar situations as dangerous. That’s survival. But in modern medicine, it backfires.

The Hidden Cost: Medication Discontinuation

The nocebo effect isn’t just uncomfortable - it’s expensive. Up to 20% of people stop taking effective medications because they think they’re having side effects. In reality, many of those symptoms are nocebo-driven.

Imagine this: You’re on a drug that works. Your blood pressure is stable. Your depression is under control. Then you read a leaflet that says, "May cause weight gain, fatigue, and sexual dysfunction." You start noticing every little ache. You think, "This isn’t working." You quit. Your condition worsens. You end up on a new drug - maybe more expensive, maybe with worse side effects. And the cycle continues.

Healthcare systems lose billions each year because of this. Pharmaceutical companies lose sales. Patients lose health. And it all starts with a warning that wasn’t necessary.

How Doctors and Pharmacies Are Fighting Back

Some clinics are changing how they talk about side effects. Instead of dumping a long list, they use what’s called "balanced framing":

- Instead of: "This drug can cause headaches in 1 out of 10 people."

- They say: "Most people tolerate this well. A small number may get a mild headache - usually just for the first few days. If it happens, let us know. It usually goes away on its own."

Studies show this reduces symptom reporting by up to 30%. It’s not hiding risks. It’s managing expectations.

Training programs in New Zealand and the UK have taught doctors how to spot nocebo triggers. After 4-6 hours of communication training, doctors saw fewer patients quit their meds. In one NHS pilot, adverse event reports dropped by 14%.

Even pharmaceutical companies are starting to pay attention. The FDA now asks drug makers to consider expectation effects when designing clinical trials. The European Medicines Agency is updating leaflets to reduce fear-based language.

What You Can Do If You’re Starting a New Medication

If you’re about to begin a new drug, here’s what helps:

- Don’t read the leaflet before you start. Wait until you’ve been on it for a few days. Your brain won’t be primed to look for problems.

- Ask your doctor: "What side effects do most people actually experience?" Not "What are all the possible ones?"

- Give it time. Many side effects fade in 1-2 weeks. If you feel off, wait. Don’t assume it’s the drug.

- Track your symptoms. Write down what you feel - and when. Is it really linked to the pill, or just stress, sleep loss, or caffeine?

- Don’t Google it. Search "side effects of [drug name]" and you’ll see horror stories. Your brain will latch onto them.

Remember: feeling a little off doesn’t mean the drug is broken. It might just mean your brain is reacting to fear.

The Bigger Picture

The nocebo effect isn’t about patients being irrational. It’s about how we’ve designed healthcare. We assume more information = better care. But sometimes, too much detail backfires. We list every possible risk - even the ones that happen once in a lifetime - and wonder why people stop taking their meds.

The solution isn’t to hide risks. It’s to communicate them better. To say: "This is what most people feel. This is what’s rare. This is what’s temporary. This is what’s real."

As researchers like Professor Karin Jensen and Dr. Keith Petrie point out, your brain has its own pharmacy. It can heal - or harm - based on what you believe. The nocebo effect proves that. And if we learn to work with it, not against it, we can make medications work better - for everyone.

Can the nocebo effect cause real physical symptoms?

Yes. The nocebo effect isn’t just "in your head." Brain imaging shows that negative expectations activate the same areas involved in pain and nausea - the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and prefrontal cortex. People report real headaches, fatigue, dizziness, and stomach issues - even when taking a sugar pill. The body responds to belief as if it’s a chemical trigger.

Is the nocebo effect the same as hypochondria?

No. Hypochondria is a persistent fear of having a serious illness despite medical reassurance. The nocebo effect is a specific reaction to expectations about a treatment. Someone might take a new medication, read the leaflet, and start feeling nausea because they expect it - not because they think they have cancer. It’s triggered by context, not generalized anxiety.

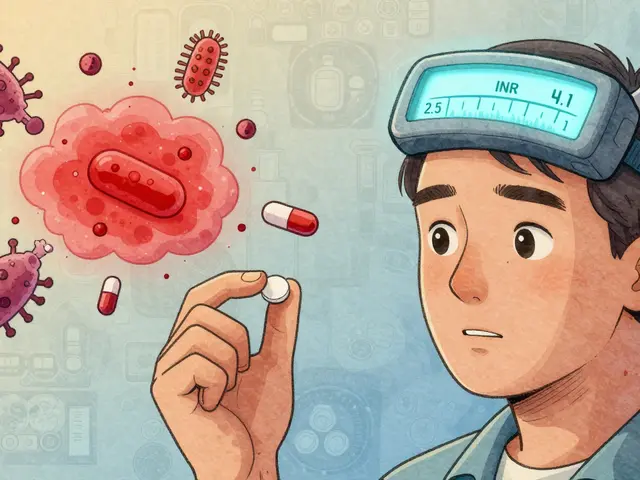

Why do generic drugs seem to cause more side effects than brand-name ones?

They don’t - chemically. Generics have the same active ingredient, dose, and absorption rate. But if patients believe generics are "inferior," or if they hear stories about side effects after a switch, their brains can trigger real symptoms. Studies show this happens after media coverage or pharmacist warnings. The drug hasn’t changed. The expectation has.

Can doctors reduce nocebo effects without hiding risks?

Yes. Instead of listing every possible side effect, doctors can use balanced framing. For example: "Most people take this without issues. A small number may feel mild nausea for a few days - it usually passes. If it lasts more than a week, let us know." This keeps patients informed without priming them to look for problems.

Do patient information leaflets make nocebo effects worse?

Yes. Leaflets often list every rare side effect - even those occurring in 1 in 10,000 cases. Research shows that the longer the list, the more symptoms patients report. One study found that changing the leaflet to highlight common effects and downplay rare ones cut symptom reporting by nearly half. Transparency matters, but so does context.

Understanding the nocebo effect changes how we think about medication. It’s not just chemistry. It’s psychology. It’s communication. And it’s powerful enough to make a sugar pill feel like poison - or a real drug feel like magic.

Tola Adedipe

8 Feb 2026 at 02:05Bro this is wild. I was on generic sertraline and thought I was losing my mind-insomnia, sweating, weird brain zaps. Went back to brand-name and poof. Gone. Turns out my brain was just scared because the pill looked different. Nocebo? More like no-thanks-to-my-anxiety.